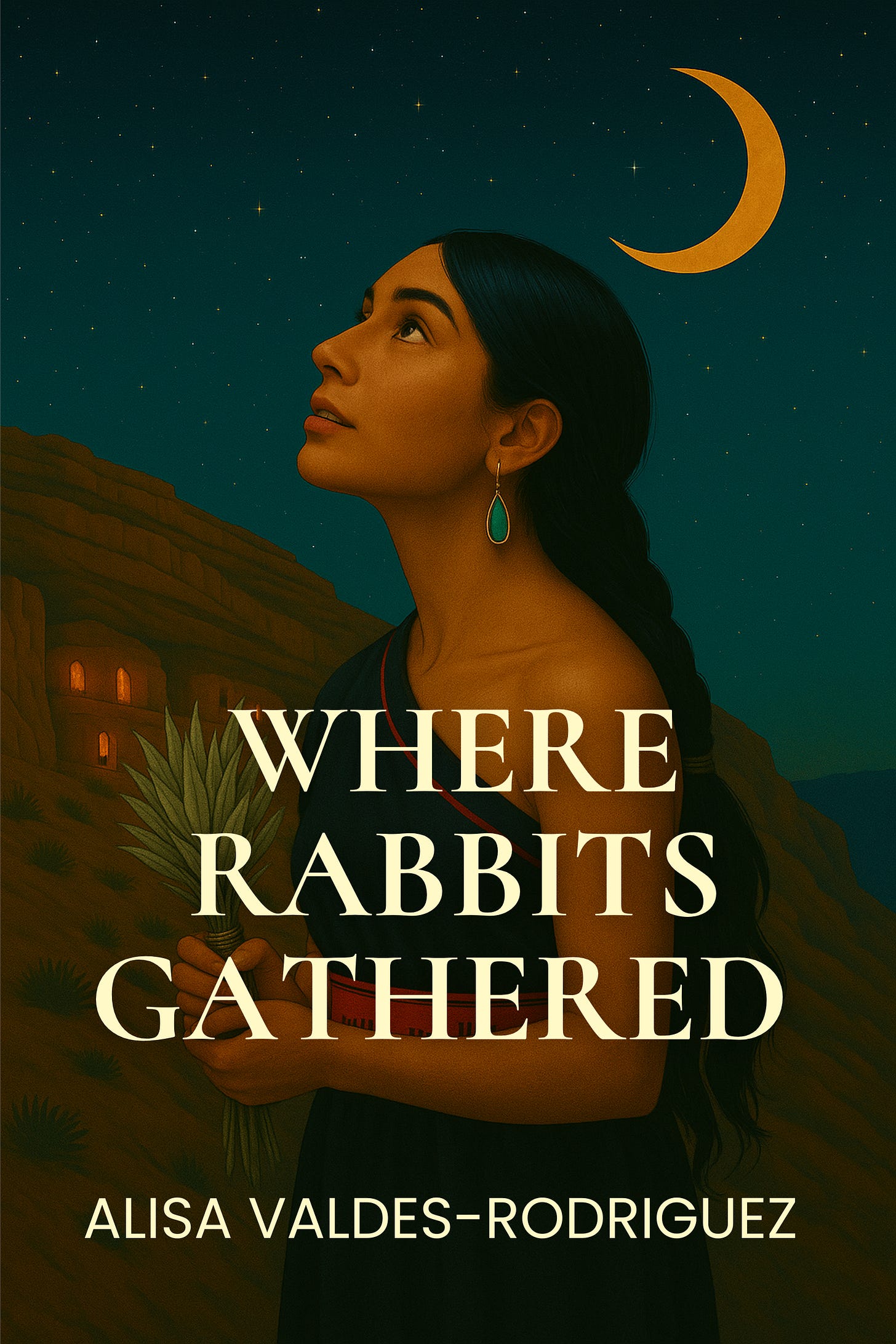

Book Giveaway and Reading!

I wrote the historical novel Where Rabbits Gathered to examine a way of surviving that sits outside the familiar European and American story of dominance. In the culture many of us were raised in, cultural survival is framed as winning or losing, conquering or being conquered, overpowering or being erased. Simple binaries. Violence is treated as proof of strength. Control is treated as success. History is often told as a series of battles that determine who mattered and who did not.

The Puebloan peoples I write about tell a different story.

The novel looks at the first hundred years of Spanish invasion of Tewa and other Puebloan communities in what is now northern New Mexico, and it’s based on my own family history. It opens in 1580, during a period of calm in the Tewa cliff dwelling city of Puye, decades after Coronado’s brief and damaging expedition, when daily life has returned to something recognizable and whole. The Spaniards are remembered dimly, as a strange disturbance or bad dream from the past. Ceremonies continue. Families grow. The world feels stable again as it has for tens of thousands of years here.

That sense of normalcy is essential, because it shows what existed and endured before Juan de Oñate arrived with a far more aggressive and permanent campaign of occupation.

I’m directly descended from several members of Oñate’s expedition, with my first documented Spanish ancestors arriving in what’s now New Mexico in 1598. Though my ancestry is primarily Spanish and Irish at this point, there were also Puebloan women ancestors, 8 to 13 generations back, likely women who were forced into “marriage” to Spaniards.

I wrote this book as a sort of atonement for the sins of my Spanish ancestors, an apology, a reckoning, and a call to my Indigenous ancestors, to say I’m listening and want to hear their stories. I will not look away from what my Spanish grandfathers did. I will not sanitize what happened here. I will not celebrate the brutality, nor downplay it. I will hold it and mourn.

One of the earliest scenes in the book is a Tewa naming ceremony for a newborn child. The women of the father Sun Elk’s birth clan come to the mother to offer names, after four days and nights of her holing up alone in the dark with her newborn. Presented with the names, the mother chooses one from among them.

Tewa society is matrilineal, and husbands join their wives clans with marriage. But the women of his birth clan are tasked with naming his child, so he and the baby remain also deeply connected to the father’s people. Kinship flows across families and generations, held together by clan mothers who carry memory, authority, and continuity.

Puebloan societies, particularly through their matrilineal cosmological structures, emphasize cooperation, tolerance, flexibility, allowing for difference, and respectful incorporation of other people’s beliefs rather than a brutal insistence upon sameness. Authority is relational rather than absolute, and inclusive of the entire living world. Identity is layered rather than rigid, because there is no Angry Sky Daddy threatening to smite and destroy. The origin story is rooted in communication, kindness, community, decency, beauty. Beauty and responsibility are not just sentimental values; in the unforgiving, stunning mountains of the high desert, they are practical strategies for endurance. These systems allow cultures to absorb change without losing themselves, to adapt without disappearing.

Centuries later, the results are visible today. Puebloan peoples, cities, and cultures are still here. Tanoan-Keresan languages are still spoken. Ceremonies continue. Spain, as an imperial force in this region, is gone. Even the Spanish language is disappearing, replaced by English. This endurance did not come primarily through ongoing violent resistance, though there was a major uprising that succeeded. It came patiently across five centuries, through an adaptable cosmology that valued respectful balance over domination, continuity over conquest, and relationship over control.

This is what Where Rabbits Gathered is ultimately about. It is not simply a novel about the injustice and brutality of the invasion. It is a novel about an alternative path through brutality, toward survival, one shaped by women, by land, and by a worldview that refuses the false choice between submission or annihilation. It asks what happens when a culture survives not by becoming meaner and more rigid, but by becoming more cautious, more secretive, more loving. I think of the Buddhist parable about the rigid reed in a storm, versus the reed that bends. Only one endures.

Today’s reading comes from the beginning of that story, before the rupture fully arrives, when life still follows its own internal logic. I’m also offering a signed copy of the novel as a giveaway, an invitation to spend more time with a world that has something vital to teach us about endurance, even now.

To enter the drawing for a signed copy of Where Rabbits Gathered, leave a comment on this post and tell me a tradition that has carried meaning in your own family or culture. I’ll choose one winner at random and announce it in next Tuesday’s newsletter.

Join me for a live reading from the novel at 6 p.m. MST today!

hi alisa, I started reading your posts when I realised you write of new Mexico and the communities and places that are part of my family history. I'd really love to read your book and learn more about my ancestors.

my family tradition is to make Christmas. tamales with New Mexican Chile, no other Chile will do. there is something about soaking the chiles, removing the stems and some seeds, and blending them with water, garlic and salt that feels like tradition passed on through the ages. tho I know my ancestor grandmothers used a molcajete to create the Chile paste. it is Christmas when the smell of New Mexico Chile is in the air!

I look forward to reading your book!