Language is not neutral. It’s a tool, a weapon, and often, a disguise. For writers, language is the medium through which we reveal or obscure truth. And nowhere is this duality more apparent than in the passive voice—that insidious construction that allows actions to float unmoored from accountability, obscuring the hands that commit atrocities. (The passive voice, for those unfamiliar, is a grammatical construction where the subject of the sentence is acted upon rather than performing the action, often obscuring responsibility.)

Take the headlines this week, as reports trickle out of Gaza about babies freezing to death. “The babies are freezing to death,” or “Gaza babies are dying,” the headlines read, over and over, as if the babies themselves have agency and are somehow responsible for their own deaths. This passive construction is more than just poor writing. It’s a deliberate act of erasure. The babies—those tiny, defenseless beings—are not freezing to death by choice or accident. They and their families are being murdered, systematically, by a genocidal blockade imposed by the Zionist Israeli military that forced them from their homes, destroyed those homes, put the people in camps, then denied aid, including blankets, to reach those camps. By framing these deaths as something that babies are doing, the headlines absolve the perpetrators who are doing it to the babies, rendering them invisible. Babies are not freezing to death; Israel is murdering babies.

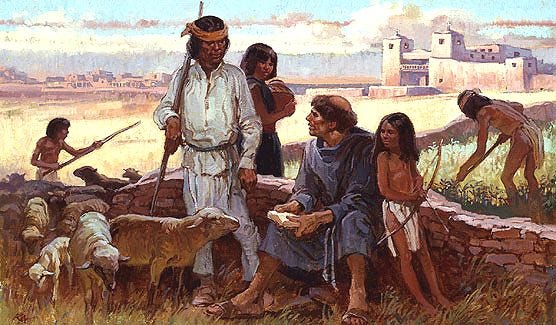

This is not a new trick. The passive voice has long been the favored syntax of empires and oppressors. When European colonizers swept across what is now the United States, committing genocide against Indigenous peoples, how was it recorded in the dominant narratives? How is it still told today? We are still being told that Native Americans “mysteriously disappeared,” as though they were wraiths vanishing into the fog. No mention of the violence, the stolen land, the forced removals, the mass murder, the forced starvation, the smallpox-infected blankets in weather where, without blankets, babies might… be frozen. To death. Just a vague, ethereal absence of people who used to be there. The passive voice doesn’t just distort the truth; it denies humanity to the victims.

When you study writing formally—be it creative writing or journalism—one of the first lessons is to avoid the passive voice. “Use strong, active verbs,” professors and editors drill into their students. And yet, in certain industries—law, politics, corporate PR, the military—the passive voice is the preferred norm. Why? Because it weakens accountability. “Mistakes were made,” say politicians caught in scandals. “Collateral damage occurred,” says the military after a drone strike kills children. The passive voice is not just lazy writing; it is strategic obfuscation.

In journalism, I saw this firsthand. Twenty-four years ago, I walked away from a coveted staff writer position at the Los Angeles Times after ten years as a news reporter. I left because I could no longer participate in the kind of linguistic manipulation that headlines like “the babies are freezing to death” represent. It outraged me then, and it outrages me now, that such phrasing—sanitized and passive—is presented as fact in the nation’s most respected publications. It’s not fact. It’s spin, crafted in service of power, in service of empire. I’ll never forget the time I was a reporter at the Boston Globe, assigned to write about the United States government “controlling” the “wild horse population.” The press release was written with such distrubing sterility, with no compassion for the horses who were being shot from helicopters. I wrote that the horses would be killed, and the government tried to sue the newspaper over my word choice. They know what they’re doing.

This is why I turned to novels. Fiction, for all its invention, offers a freedom that journalism does not. In fiction, I could tell the truths of erased peoples, the realities that official records and news reports twist or ignore altogether—or sue me for trying to make public when to do so would make someone powerful look bad. If you want to understand the truths of a time, read its novels. When Charles Dickens wrote about child labor, he exposed the brutal realities of industrial England, even as newspapers of his era treated child labor as an unremarkable fact of life. Novels don’t just tell stories; they bear witness.

And so, I bear witness. To the babies in Gaza, whose deaths are not “freezing” but murder. To the Puebloan women and children in New Mexico, whose suffering under Spanish colonizers was not a “mystery” but a brutal reality. These are the truths I tell in my work, truths that cannot be contained within the euphemisms of passive voice.

If you’re ready to confront the truths that history textbooks and mainstream media have often ignored, I invite you to pre-order my upcoming historical novel, Where Rabbits Gathered. Through the eyes of six generations of women, the book reveals what the Spanish really did to the Puebloan people between 1580 and 1680 in New Mexico. It’s a story of resilience, resistance, and the human cost of empire. Because sometimes, fiction is the only way to tell the truth.

Language shapes reality. And reality demands that we speak the truth, clearly, directly, and without the veil of passivity. Babies are being murdered. Say it. Write it. Refuse to let the headlines erase it.

Where Rabbits Gathered will be released through my publishing house, Tomé Hill Press, on April 22, 2025, but every preorder will go towards the first week’s sales figures. Money talks. If you support the way I see the world, please support my work. You can also do so by subscribing to this newsletter for $10 a month.